Better Betting with Warren Buffett

Market Perspectives – August 2018

August 14, 2018

Market Perspectives – September 2018

September 10, 2018

By: Dustin Barr, CFA

On January 1, 2008, Warren Buffett entered into an agreement with hedge fund firm Protégé Partners (then run by Ted Seides). Mr. Buffett had previously openly offered to bet anyone who wanted to come forward that they couldn’t beat the S&P 500. Mr. Seides was the only person courageous enough to do so. The terms of the bet were as follows:

- Seides had to pick five “funds-of-funds” that would in turn invest in multiple hedge funds. There were more than 200 hedge funds represented. Mr. Buffett simply picked the S&P 500.

- At the end of 10 years (December 2017) the investment with the highest return wins.

- The stakes were $1 million to be donated to the charity of the winner’s choice.

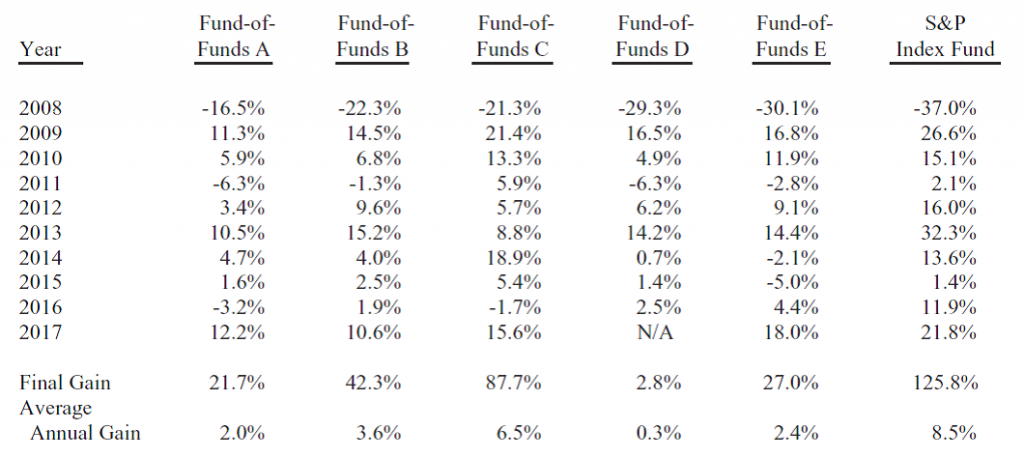

After ten years, here are the results from the Berkshire 2017 letter:

Source: Berkshire Hathaway Annual Letter – 2017

The S&P 500 delivered an annualized return of 8.5% while all five funds of funds returned between 0.3% and 6.5%. It should also be noted that one of the five funds actually liquidated (went out of business). The results are nothing short of a drubbing. Mr. Buffett has used the results to take a very public victory lap in his recent letters.

Many have opined on the bet. The consensus message in the industry has been this: “hedge fund managers charge a lot of fees and destroy value for their clients.” Here at CIC, we have not commented on this topic previously and we thought it would be a good time to discuss it. Here are my thoughts:

- The term hedge fund is often misused. All hedge funds are not the same; in fact there are many types and some aren’t even “hedged.” A traditional hedge fund is a “long/short” fund meaning they can buy stocks and they can sell stocks short (bet that the stock will drop). Others include merger arbitrage, distressed credit, trend following futures (CTA), risk parity, and many more. However, for the sake of this conversation we will focus solely on equity long/short when we refer to hedge funds.

- Credit Suisse aggregates the hedge fund universe and the average beta is 0.41 over the last 10 years (source: Morningstar Direct/Credit Suisse Long Short Index). To put this in context a beta of 1.00 means the investment has a risk level equal to the S&P 500 (this is admittedly overly simplified). If markets are fully efficient, one would expect an investment with a beta of 0.41 to deliver returns over a market cycle: Cash Rates + (0.41 X (S&P 500 return – Cash Rates)).

- Even if fees weren’t high, it wouldn’t be very easy for a fund with such low risk to have a higher expected return than the market.

- Over the 10 year window of the bet, if the market was perfectly efficient, we would expect the average hedge fund to have delivered 3.3%; two of the five funds-of-funds above did that. If the funds charge 2% fees and take 20% of the excess profits, they will need to generate far better returns than just 0.41% of the S&P 500 to get to the 3.3% net of fees. In fact, a 3.3% return over 10 years would result in just 0.04% (including a 1% feeder fund fee). Meaning if all of the funds in the bet delivered the expected risk-adjusted return, the investor would be left with nothing!

- The funds in the bet averaged 2.96%. If we add back all of the fees we could assume the managers delivered 6.95% on a gross of fee basis. That could leave one to assume the managers may have had decent skill considering we would have expected 3.3%.

- So what would it have taken for Mr. Seides to win the bet? In doing the same exercise as above, to get to 8.51% annualized net return, the 200 hedge funds would have had to deliver a total return of: 13.9% average annualized returns!

A few closing thoughts:

- Buffett was on the right side of this bet, not because hedge funds are inherently bad investments, but rather the hedge funds don’t inherently have a higher expected return than index funds. If the bet was measured by risk-adjusted performance (adjusted by volatility or beta) it would be a fairer fight.

- Buffett required that Mr. Seides choose funds-of-funds. In aggregate, there were as many as 200 hedge funds in the return numbers. Having this many funds in the lineup likely meant that Mr. Seides was highly diversified. This probably reduced his odds of overcoming the fee and risk hurdles.

- Certain types of hedge fund strategies can add value for investors but an investor should know what they are getting themselves into. Investors should be wary of high fees, they should understand the strategy and why they own it, and they should find an appropriate benchmark to measure the strategy.

- Finally, I disagree with Mr. Buffet on three major points.

- Most investors shouldn’t hold 100% stocks or anything close to this level of risk. Countless studies have concluded that the average investor generates returns that are far below returns of the stock market and of balanced portfolios. The volatility of an all stock portfolio is too much for most to handle. There are ways to diversify a portfolio to smooth out investor experiences without giving up too much in expected returns.

- While we believe in indexing, not all capital markets are as efficient as the U.S. stock market. We believe pairing index strategies with active managers who have proven track records of adding risk-adjusted returns over a full cycle can and has added value historically.

- Lastly, we think Mr. Buffett is using the wrong index. The S&P 500 has only U.S. large cap stocks. History tells us that having all of your investments in one country comes with its own risks. We advocate for a global positioning and think the MSCI ACWI or some mix of the S&P 500 and the MSCI ACWI ex USA would be a better benchmark.

Dustin Barr, CFA is a Consultant & Director of Research at Carolinas Investment Consulting. He oversees the CIC Investment Committee and manager research and due diligence process at the firm. He provides investment & financial advice to families, non-profits, and corporate retirement plans. Click here to learn more about Dustin and how he can help you.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Carolinas Investment Consulting. All data sourced from Morningstar Direct unless otherwise noted. The information published herein is provided for informational purposes only, and does not constitute an offer, solicitation or recommendation to sell or an offer to buy securities, investment products or investment advisory services. All information, views, opinions and estimates are subject to change or correction without notice. Nothing contained herein constitutes financial, legal, tax, or other advice. The appropriateness of an investment or strategy will depend on an investor’s circumstances and objectives. These opinions may not fit to your financial status, risk and return preferences. Investment recommendations may change and readers are urged to check with their investment advisors before making any investment decisions. Information provided is based on public information, by sources believed to be reliable but we cannot attest to its accuracy. Estimates of future performance are based on assumptions that may not be realized. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future returns. The following indexes were used as proxies in the performance tables: Global Stocks = MSCI ACWI; U.S. Large Cap = S&P 500; U.S. Large Value = Russell 1000 Value; U.S. Large Growth = Russell 1000 Growth; U.S. Small Cap = Russell 2000; Int’l Dev Stocks = MSCI EAFE; Emerging Markets = MSCI EM; U.S. Inv Grade Bonds = Barclays U.S. Aggregate; U.S. High Yield Bonds = Barclays Corporate High Yield; Emerging Markets Debt = JPMorgan EMBI Global Diversified; Int’l Bonds = Barclays Global Treasury ex US; Cash = 3month T-Bill; Sector returns displayed in the chart represent S&P 500 sectors, while treasury benchmarks are from Barclays.